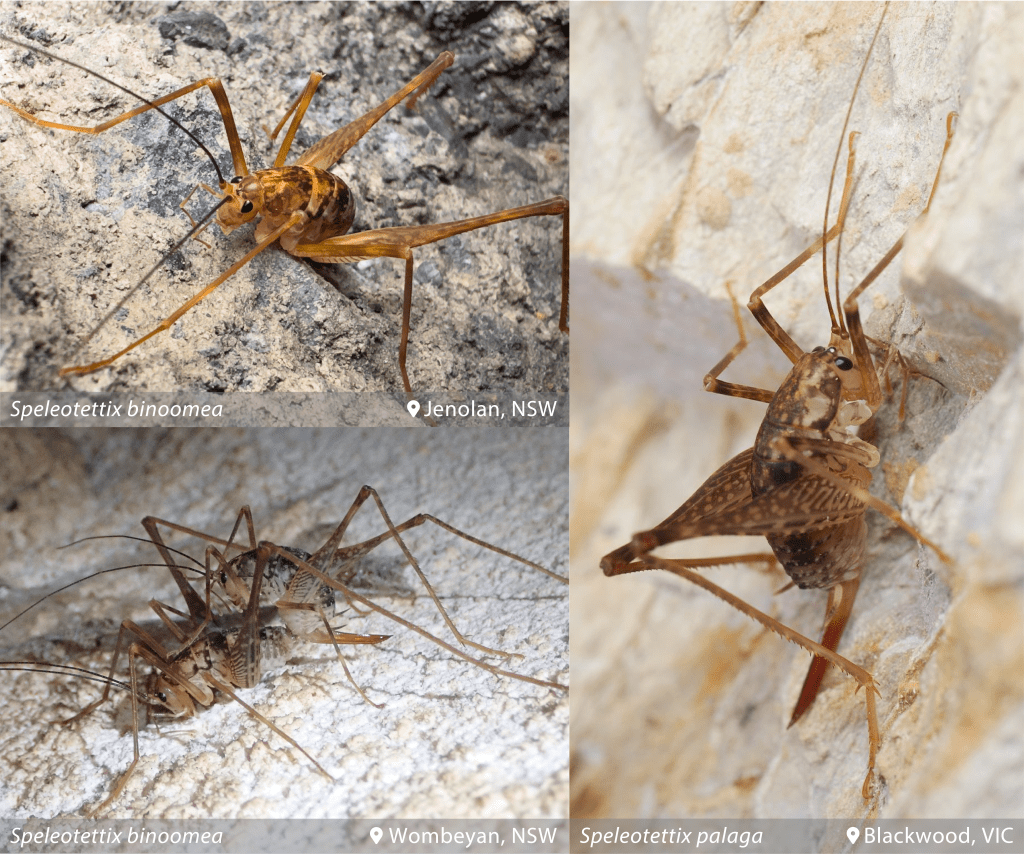

Three new species of cave cricket have been named in a taxonomic paper by ISB members Dr Perry Beasley-Hall (lead author), Dr Brock Hedges, Prof. Steve Cooper, and Prof. Andy Austin. Published in Austral Entomology, the paper tackles the taxonomy of Speleotettix, a genus that was poorly studied even by Australia’s previous authority on the group.

But what are cave crickets? And why should we care about efforts to further uncover their biodiversity?

Is that a spider?!

Cave crickets are an ancient, nocturnal group of insects found worldwide with cartoonishly elongated legs and antennae. You might have heard of them as cave wētā, their common name in Aotearoa/New Zealand, but they’re a separate group to the chunky crickets with the same name.

Even though these insects might look a little scary, any resemblance to spiders is superficial: their spindly appendages only serve to help them navigate a life in almost complete darkness.

Room service underground

Caves, and other underground environments like them, tend to be very nutrient-poor. Plant life can’t be sustained in the dark, so as you move deeper and deeper into a cave, the less food you’ll find.

If you’re a species dependent on caves to survive, how do you eat? You can either 1) become a scavenger, eating anything and everything, or 2) venture above-ground to find food. Cave crickets use both of these strategies.

By foraging in the outside world, these insects act as cave “room service” by re-injecting an otherwise starved environment with external energy in the form of their bodies, eggs, and poo. This means cave crickets are often considered keystone species: those that have a disproportionately positive impact on their surrounding environment.

Robust cave biodiversity has been positively associated with cave cricket populations and they’re the primary food source of a wide range of predators.

Species in decline?

In Australia, cave cricket biodiversity is poorly understood but anedoctally declining. Populations once in their thousands have disappeared from popular tourist caves; species restricted to single islands haven’t been sighted for years; and colonies appear to be very sensitive to human disturbance. The biggest threats to these animals include native forest logging and clearing, climate change, and ecotourism (when practiced irresponsibly).

To begin conserving Australia’s cave crickets, first we need to generate baseline data on how many species are out there and where they occur. This also includes naming new species and redescribing others.

Our new paper focused on Speleotettix, the only genus of Australian cave cricket not studied by the previous expert on the national fauna, Dr Aola Richards (1927–2021). As a result, identification resources for the genus are lacking and its species are more poorly known than others.

This gave us the opportunity to clean up the taxonomy of several existing species but also meant we discovered three new ones:

- Speleotettix aolae, named for Dr Aola Richards

- Speleotettix palaga, meaning “gold nugget” for the abandoned gold mine it was discovered in

- Speleotettix binoomea (BI-noo-mee), the Gundungurra word for “dark places” and the Jenolan Caves where it was found

Giving these species formal scientific names is an important first step to conserving them, but there’s much more to be done. Twenty-seven species of cave cricket are known from Australia and the true extent of the group’s biodiversity could be over double that number.

You can read our new paper Open Access here.

Leave a comment